Latinx-Caribbean Poetry

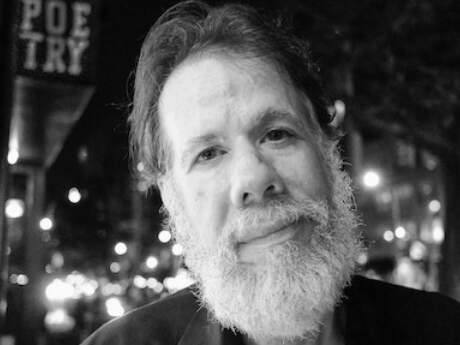

Urayoán Noel on “Heaves of Storm / Embates de Tormenta”

The poem "Heaves of Storm/Embates de Tormenta," included in my book Buzzing Hemisphere / Rumor Hemisférico (Arizona, 2015), is subtitled "(obituary for the University of Puerto Rico student strike, 2009–10, and for the poet on the sidelines)." In fact, it begins with me witnessing the 2009-2010 student strike at the Universidad de Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras (my alma mater), and wondering just how to respond.

Having grown up a few blocks from the university yet having spent most of my adult life in New York City, what was my relationship to this place and this struggle, and how could I be more than a privileged tourist, especially as a tenure-track (now tenured) professor? My relationship to the campus is intimate, as it was my playground as a child, and as my parents both taught (and met!) there. Given all that, feeling like a tourist was a terrible thing, even as earlier books of mine (such as Boringkén, 2008) had tried to write about the island from afar by invoking the tourist trope/trap with a heavy dose of (self-) irony. One way to force myself to confront the scene was to document, so I used my phone.

One day, my now-deceased father and I were walking toward the university and we came across a throng of riot police facing down the students and strikers. The scene was scary and tense. I took a few photos with the crappy phone I had at the time: the one that came out best was one with my father standing in the way and the riot police in full gear across the street beyond him. (I initially included it along with the poem, but ultimately removed it for fear of trivializing it.) It was a photo that seemed to encapsulate the many conflicting ways I was interpellated by the scene: from the intimate and familial to the geopolitical and diasporic. I didn't have a pen with me nor any clarity about the situation but I felt like I needed to respond to the moment, so I wrote down some reactions as an unsent draft of a text message. I went back to the street outside the campus a few more times (the students had shut down the campus) and I took more text notes. I kept them for a long time with no more clarity as to the scene and no expectation that they would become anything.

As I was putting together an early draft of what would become Buzzing Hemisphere / Rumor Hemisférico I realized I couldn't do a book so informed by hemispheric geopolitics and not address Puerto Rico substantively. So I went back to those texts and struggled. Other connections had revealed themselves to me by then. First, I had experienced austerity measures and program cuts firsthand while teaching at the University at Albany, SUNY. I read and shouted at protests and rallies at UAlbany and I realized that it was in some ways the same struggle. We were fighting against the same game plan and in some cases the same actors, as I discovered a couple of years later when I realized the same hedge funds were invested in gentrifying the South Bronx (where I live) and buying up Puerto Rican real estate for pennies on the dollar as austerity did its thing. This made me think in more political terms about the process of self-translation: I have been self-translating my poems for years, often aiming for a cultural politics of irreverent untranslatability, stressing the non-equivalence between languages. Yet here I wanted to open up those connections, to convey to monolingual readers that this was all part of one shared, larger struggle.

I had also read Mara Pastor's Poemas para fomentar el turismo ("Poems to Promote Tourism," 2011), one of the key books of 21st century Puerto Rican poetry, and I was inspired by how it opened up the trope of the tourist poet to the mundane and the existential as well as to the newfangled diasporas of the austerity age. I had been thinking about how the political storms of the day were inextricably bound with my inner storms, my neurodivergent experience and art. That led me back to Dickinson's "I heard a Fly buzz—when I died—," with its buzz that echoed the synaptic noise of my brain hemispheres against the backdrop of so much global buzz. Its "heaves of storm" gave me a title, and its lines gave me a structure.

I had all these bits and pieces of text notes with no order or logic, but I was able to use lines from Dickinson's poem as refrains for what became the different sections, in keeping with the pie forzado ("fixed foot"): the one-or-two-line choruses of the Puerto Rican décima, with which I have been experimenting for over two decades. That was a way of taking these smartphone notes and connecting them back to song, to the traditions of improvisational oral poetry that had inspired me growing up, and to all the music and chant and song I heard while eavesdropping on the frontlines of the strike. When it came time to structure the poem on the page, I tried to respect the look and feel of the text notes by working with lowercase lines and keeping the dashes from the original texts instead of opting for more conventional punctuation.

In the spirit of the Buzzing Hemisphere / Rumor Hemisférico manuscript, I alternated the Spanish and English versions to blur the boundaries between "original" and "translation." At the same time, I felt I needed to get to that place beyond translation where global and colonial violence meets the daily trauma, joy, and struggle of our brains and bodies. So, I followed Dickinson's "buzz" in ending the poem with a cleansing burst of onomatopoeias, with the untranslatable noise of our burning hemispheres.

***

Urayoán Noel contributed this piece in conjunction with LA BENDICIÓN: A ONE-DAY CELEBRATION OF LATINX-CARIBBEAN POETRY IN THE UNITED STATES at New York University on February 8th, 2018.