Interviews

An Interview with Joan Baez

When Joan Baez gave her Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction speech in 2017, she said, “My voice is my greatest gift…the second greatest gift was a desire to use it.”

Generations have been moved by Baez’s life story and evolution. As a teenager, she learned dark, sad American folk songs and made them cool again. She played Carnegie Hall before she was 18 years old and sang “We Shall Overcome” on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial during the 1963 March on Washington. She walked with Martin Luther King Jr. in the segregated South to integrate schools and traveled to war zones in Bosnia, Vietnam and recently, Ukraine. She went to show us what was happening, wearing a bulletproof vest and leading sing-alongs inside a bomb shelter.

When she sang others songs, she made them sound new – and she held her own as a songwriter. With songs like “Diamonds and Rust” she wrote rhapsodically about her relationship with Bob Dylan. It was, after all, Baez who basically discovered Dylan. In 1961, after she heard him perform in a Greenwich Village coffee shop for the first time, she told her taxi driver, pointing back to Dylan “That guy’s a songwriter! He’s a poet!” to which the taxi driver replied “Does he rhyme?”

Today, Baez is known as “a force of nature” by her publisher and a living legend in the 60-year-career spanning documentary “I Am a Noise.” Even in her retirement from music, she is still risking and evolving. She’s painting, drawing, and, yes, writing poetry.

When we spoke by Zoom last Friday—her in a Bob Marley shirt and her signature short hair — it was the same week her poetry collection When You See My Mother, Ask Her to Dance was released. The poems were written during a seven-year period, brought on by intense therapy. The poems toppled out of her: pages about caring for ailing family members and imagining a world where her mother could have met, and danced, with her favorite opera singer. She’s been writing about freedom, nature— especially in California—and how she finally understands, “I have a right to listen to bird’s songs.” She is continuing her journey of artistic introspection and deepening her commitment to leave, as she puts it, “an honest legacy.” She’s also making her poetry debut at 82.

In your book’s title poem, “When You See My Mother, Ask Her To Dance,” I love that you dreamed up a fictional situation where your mother gets to be swept up in romance by this Swedish opera singer Jussi Björling. What was her connection to him?

My mom loved classical music and opera. I heard his voice a lot in the house on one of those gramophones. I loved how much it meant to my mom over the years. She even took me to hear him in 1959, but he wasn't there. They say he drank a lot, so he probably was on a bender. I didn't get to see him but I loved that my mom made that effort. At one point, I realized that our initials, Jussi Björling and Joan Baez, were the same. And my mom's initials were the same. All of this crazy stuff went through my head like that his voice had been transferred to me the year that he died. In the poem, I talk about letting my hand tell the story and being a channel for it. I didn’t really write that thing. I don’t know where it came from.

With your drawings, you have said you stay open to inspiration as you make them and don’t go in with a set agenda. Is it like that for you writing poetry?

These poems were all written in about a seven-year period. I had been diagnosed with multiple personality disorder—I call it “order” because it changed my life for the better—so I had all these people running around inside me. I say that some of them made the poems because I would look at the page and think: Wow, who wrote that? It was all when I had entered deep therapy to deal with my childhood abuse. It lasted that time period, and then it was over. I can't write like that anymore. I took a year editing this little book.

Do you think of your connection to healing, creativity and spirituality as working together in your life? Are they in the same club?

Yes. I look back and think everybody was struggling in there to be heard. All my phobias and weird behavior came from, in my opinion, them not being able to just come out, just state their case and give me a chance to be whole.

You’ve said “You can't heal without being able to express yourself.”

First of all, I would recommend therapy for just about anybody. It wasn't allowed for people in my Junior High School. A psychiatrist—you kidding me? Now that's totally changed, and without any reservation, I say if you have a problem, you can't deal with, go and talk to somebody about it. You need a counselor, somebody with some brains who can listen to you and give you some encouragement or help you find a way. I was very extreme, so I used different kinds of therapists. I did art, dance, music…and throwing things. I did everything you could do.

In your poems, you're referencing Emily Dickinson and I saw there's a fun E. E. Cummings tribute and nod to Edgar Allan Poe. Are there poetic voices that have been touchstones for you in your life? I also think I read that Ginsberg came to your school for nonviolence.

Ginsberg just showed up at the institute and he also just came to the house. He was a nutcase…. I mean, he really was. Let's see, I'm not a reader. You’d think I would have read all his poetry and I haven't. So I'm sort of embarrassed about it. And then I think, Well, God dammit, I'm going to read those things. I'm going to sit in the corner of the couch the way people do and turn the light on with a book in my hand, and I can't do it. So a lot of this is lost on me.

There is something wonderful about a poetry debut at 82. That you gave yourself permission to create.

Yeah!

Do you think it comes from your background in the coffee shop era of getting up and trying things? Where do you think this impulse to try different mediums comes from?

It's more like I can't stop it. I've been on output since I came out. That's part of the thing. I pictured myself sitting cozily on the couch to read, and then I'll think, Oh, I gotta paint this! Or I've got to write this! I can't do intake very well.

I had the joy of re-reading the Joan Didion essay about you this morning about your school of non-violence that lasted for 10 years. She had just referenced poetic language that you'd written on a program for your concert called “My life is a crystal teardrop.” Then she says:

“Although Miss Baez did not actually talk this way…she does try, perhaps unconsciously, to hang on to the innocence and turbulence and capacity for wonder [...] This openness, this vulnerability, is of course, precisely the reason why she is able to ‘come through’ to all the young and lonely and inarticulate, to all those who suspect that no one else in the world understands about beauty and hurt and love and brotherhood.”

Do you think this impulse to create comes from your capacity for wonder?

Absolutely. It's that appreciation of what's surrounding me. That school for non-violence was out in the trees and the bushes. It was a place of wonder. But you can find that wonder just about anywhere.

Would you like to speak about the role of nature in your writing? Birds are a big theme in your poetry. They are even in poems about great beloveds in your life – your mother and your son.

The birds are my biggest heartache with [climate] change and the weather, and billions of them are disappearing. About 10 years ago, I thought, I can't survive that. I just can't. But if you're going to stay alive, you have to come to terms with the loss of billions of birds and two-thirds of our wildlife gone. So how do I get through the day, and not have that be crushing me? A couple of things. I don't practice it very well, but to listen to just one of those birds, and not wait for the chorus. It’s in one of the poems: there used to be hosannas, a massive chorus down this little canyon where I live. Then, one day, I came back from the tour and got up early to hear the chorus, and it was not there. That was many, many years ago.

40 years ago, I remember listening to a climate expert on some radio station who said, “There's a good possibility that in 40 years, the earth will be uninhabitable.” Well, it's been 40 years now. We're getting really close. And the biggest heartbreak out of all of it for me is the birds, because they’re my sisters and brothers. They sing.

A question that so many of us ask is how to find hope and awe and beauty in the midst of a very real despair. These are very difficult times. In the 2023 documentary “I Am a Noise,” one thing that is so striking is your dancing throughout. Would you speak a bit about how the dichotomy between joy and heartache works in your life and how to find dancing within it?

That is a nice question. Someone showed me an astrological chart after a concert and said, “Yes, you are here to sing, and to do activism, and to paint. But you're really put on earth to dance.” Yeah, I depend on it. I go through a month-long period where I get up in the morning and just dance for 15 minutes, and it's always to the Gypsy Kings.

Barefoot?

Usually barefoot. I'm lucky to live where I do, because I can go barefoot all over the property and the house. It's really beautiful.

I can't imagine talking to you today and not touching on a little bit of what's happening in the world. People are in so much pain. There's been such horrific violence against civilians in Israel and Palestine. Are there lessons from your lifetime—from the Civil Rights movement to protesting the Vietnam War draft? What would you say to folks who are grappling with this?

I would say that back then I had people around me who were smart enough to let me know that “We Shall Overcome” does not mean we will do that overnight. Peace doesn’t come right away. It means that you do it in increments. And [the Civil Rights Movement] was a huge increment. And now, the scenario is something we could never have dreamed of. It's so fucking awful.

So, I would say to those kids on the campuses now: choose what you're going to hang onto, like divestment. Then you stay with that and you make your “good trouble” right there. It's very difficult to work uphill in an avalanche, which is where we are. It is the decade of the bullies and that's what's expected as normal.

Why was it important to write about caring for your parents and sisters as they were aging, who have now passed away—and why do you want to leave an honest legacy?

I've got nothing to lose now. My family's gone, I won't hurt anybody. And I thought, okay, what can I contribute? It would be an honest legacy. And it's really interesting. The response to the documentary has been interesting. People say it's so honest, but it shouldn't be a big deal. But it will help other people, I think, say their truth more than they're doing now.

What is the process of writing a song versus writing a poem?

For whatever reason, they're very different. I thought, I got these great poems. I'm gonna make songs out of them. But it doesn't really work that way. I don't know why. And I spoke with other songwriters who agreed with me. I wrote a song about Lily, but it was very contrived. I was trying to stuff all this stuff into music, and it didn't really work for me.

So sometimes, the poem is the right form for the idea?

Yeah. It's probably in some ways a relief to do the poetry. You don't have to match it to the music.

Is there anything you’d like to say about trusting your feelings, your intuition, and maybe not always having the answer?

What's coming to my mind is what a woman told me about painting, and it probably applies to other things. She said, “Make as many mistakes as you can!” When I was painting, if I was having trouble making sense out of it, I would dunk it in a swimming pool. And whatever happened happened and I’d work from there. That gave it a certain life that it didn't have before.

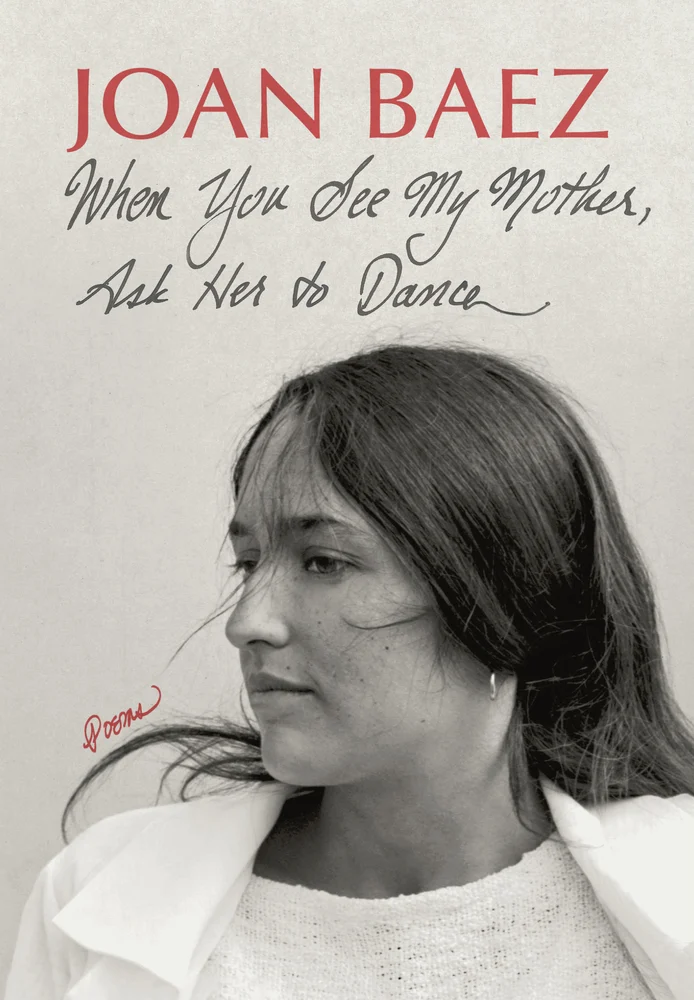

On the cover of your poetry book is a picture of you at the Newport Folk Festival. Is it right before you went on stage for the first time?

I don't remember. All I know is I still have my baby fat.

Inside the back cover, we see a picture of you now. You’ve said this is your favorite decade so far. Why is that?

I just go on shedding stuff I don't need. Psychologically. Physically. It gives a lightness to my life. I somehow realize I have a right to sit out there and listen to birds. I don't have to be doing something else. Probably more freedom. I mean, aging is pretty scary. You have just got to deal with it as it comes along. My balance stinks. One of these days I'll probably use a cane and I’ll have to get to like the cane.

For people in later seasons who might be inspired to make their debut at something, what would you say to them?

You’ve got nothing to lose. Do whatever impulse comes up. If it's painting, if it's building a bridge, it doesn't matter. Just do it while you have time.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity

BIRDSONG

by Joan Baez

I lay out on the porch in the dark

in my warm and rumpled sheets

awakened by the moon-sliver

casting glimmers on the hibiscus.

It is time for the most beautiful music to begin.

Heart awaiting, every nerve listening.

But by dawn’s light, we heard it not

and my breath grew silent, but we heard it not.

I was perched in a nightdress

at the edge of the veranda in anticipation.

But we heard it not. Yes, today was

the day the birdsong suddenly stops.

Last year it was on the fifteenth of June,

so I’d hoped I had more time.

But when I could distinctly make out

tree against tree on the mountain across the canyon,

I knew it was true: there was no flood, no chorus.

Only cheeps and peeps, chirps, squawks, and eeps.

But the ringing of hundreds of silver throats would not

come again until spring—if they ever come at all.

I told myself, “It is nature . . . the birds

have business . . . or are tired.” I held my breath.

I can barely stand the inevitable turning

of the seasons and the remnants and shadows

of the hosannas that filled the canyon

only yesterday.

“Birdsong” from When You See My Mother, Ask Her to Dance. Copyright © 2024 by Joan Baez. Reprinted by permission of Godine.