Interviews

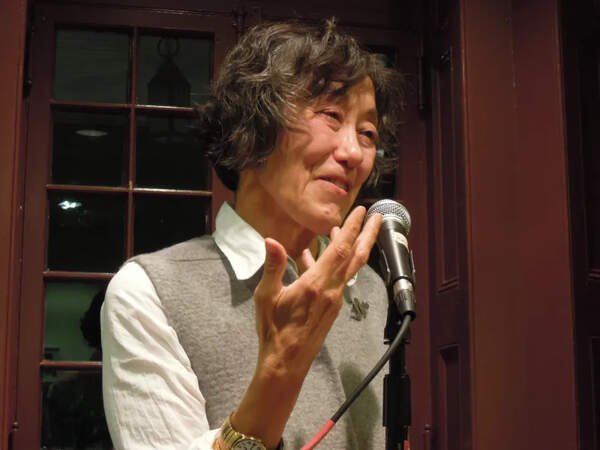

An Interview with Diane Seuss

Jennifer Franklin: In reading both frank: sonnets and Modern Poetry, I find a mind deeply engaged in grappling with meaning and making sense of the past through poetry. These are deeply personal poems yet they are not what we think of as confessional. They feel archetypal. How do you decide what details to include and what to leave out? Is it intuitive?

Diane Seuss: Hmmm. That’s a tough one, Jennifer. I’ve been writing for so long, I do have an intuition that follows me, or that I follow, in my writing practice, just as I’m sure you do. Maybe the key to the archetypal, as opposed to what is called confessional, is a sort of objectivity about the poem itself—the poem as object, in the way that a clay pot is an object, or a Grecian urn. That sense of the poem as an objet d'art as opposed to a language spill, or a speech act, helps me think about even the most personal material as just that—material. There is a positive coldness that sets in when I write. That wasn’t always the case. I think it developed over time as a response to events that were too difficult to manage as confession. I needed to build an urn that would exist beyond me.

Jennifer Franklin: When you read for the Hudson Valley Writers Center recently, we spoke a little about the way in which so many of your poems throughout your books, especially in frank: sonnets and Modern Poetry, but also in Four-Legged Girl and Still Life with Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl, are a balance of embodied experience and intellectual experience. You love Keats’s poetry and, through the collection, the speaker also loves Keats as the concept of a great Romantic figure who died of tuberculosis in Rome when he was twenty-five, pining for his love, Fanny Brawne. Perhaps part of the attraction is that you were so young when you discovered Keats and his words kindled a passion in you. Like Eliot says, “great poetry is felt before it is understood.” But you really love Keats. You write about your speaker visiting his death room in Rome and kissing his death mask on the mouth until her lips are covered with the white plaster. It is such a powerful moment of the book and it reminds me of the thesis of my undergraduate mentor. His theory is that our idea

of the people we love haunts us, animates us, lives inside of us. They are often more real to us than the people sitting across from us at the breakfast table. I have a similar passion about writers I love and, sometimes, I wonder if part of it is that they are dead and they can’t disappoint or betray us. Can you speak a little about this passion for Keats and what kind of sustenance it has given you over the years?

Diane Seuss: Ooh. You got me, girl. I think that is so true—the dead are much more reliable than the living. Though in Modern Poetry, there is a poem, “Pop Song,” in which my father, who’s been dead since I was seven, has become distant from me. In the poem, he’s disappointed in who I turned out to be. Just my being alive is too weighty for him. He’s like: “Later, Di.” I encountered the possibility that the dead, too, evolve in their understanding. I think the dead rise into our imaginations as archetypes; memory imbues them with plaster dust and lipstick. In art, they can then serve our purposes. I love Keats in many ways, but none of them are the kind of love I’d have for a living person. I love the letters he wrote, the ardor, the fervor, the way he concocts ideas—like Negative Capability—that rock our worlds. I love him for his suffering, for his despair about his legacy, or lack thereof. I love his steadfast belief in poetry, and the way he was in love with romantic love. I love the idea of Keats. The idea of Keats fed Modern Poetry in a way no living person could. The poem in which the speaker—a version of the young me—kisses Keats’s death mask, was a leap for me through time and space, even an ethical leap. I hope the poem earns it.

Jennifer Franklin: In an earlier poem, “Self-Portrait with Sylvia Plath’s Braid” you write,

“In the dream I fasten

her braid to my own hair, at my nape.

I walk outside with it, through the world

of men, swinging it behind me like a tail.”

There is a strong sense of legacy in the poems in which you write about other poets, and the way you have stitched your poetic contributions to the poems and poets you love who have come before you. Can you speak a little about the deep connection you feel to dead poets? And what relation does the idea that “the dead don’t love the living. / Like Jesus, they judge us.” Specific dead people haunt the collection—Keats, the speaker’s father, some friends who have died. Even the love object of the speaker’s son is dead. He is in love with Anne Frank, and in “An Aria” you write, “My son’s first love was Anne Frank / after he read her diary. He was eight, drawing portraits of her day and night. / I must have Anne, he said when I tucked him in, / though he knew she was dead, whatever that means.” Can you speak a little about what role the dead has in this collection and the thin veil between the dead and the living for the people in the world of this collection? How does the connection to dead family and friends connect to dead strangers only known through their words?

Diane Seuss: Well, hopefully I can extend my response to your last question into new territory, here. Probably I have always felt, as least since early childhood, like part of me belongs with the dead. Anyone who has lost a parent or sibling in childhood will know what I mean. Also—and this is difficult to explain—the world I lived in was not falsely disconnected from death. We lived next to the village cemetery. Mourners walked by our front window every day, having made their way by foot from out in the countryside, to visit their dead. One rail-thin woman wore a long black coat, black four-buckle boots, and a black veil, with lamp black smeared on her face. I thought, from my vantage point, she might be a crow. We were tucked within a tight ecosystem of bog, small inland lake, and pasturelands. Lily pads and bullfrogs and cows. The daily work of butchery—gutting fish, butchering hogs, hanging chickens on a clothesline, and beheading them, the bodies running headless until they ran out of steam. So yes, the veil between the living and the dead is thin. To have a quorum, in places like that, one must include the dead. As Kevin Young writes in his wonderful essay, “Deadism,” we can “write a poetry that is not like death, but is death…Write not like a coming extinction, but like the extinction already… a poetry that speaks from the mouths of those gone that aren’t really gone, a poetry of ghosts and haunts. Of haints: not ain’ts.” How can we study the literature of the past without courting a relationship with the dead? And yes, Dylan, my son, learned that young, after he read Anne Frank’s diary. He fell in love with her. Maybe it’s a family tradition. In Modern Poetry, the dead receive the gift of objectivity about the living. That is a notion I never explored before.

Jennifer Franklin: The connection to the dead writers (John Keats, Colette, Anne Frank) are so embodied. It’s part of the reason that you were the first person I thought of when soliciting poems for the Braving the Body Anthology. I live with a lot of complications from tongue cancer and radiation treatment, including chronic pain and a chronic cough, requiring voice and swallowing therapy, as well as mild EDS, which necessitated two partial knee replacements, and I think all the time about the lines in “Against Poetry” where you write, “Mine is the kind / of body you drag around / town on a leash with a choke / chain. You don’t love it / but it’s yours to contend with / though it compresses your / soul.” The speaker talks a lot about her body in this book, and it seems that it’s often in opposition to the mind. I wonder if you can talk about that mind-body juxtaposition in these poems.

Diane Seuss: First, let me say I am sorry for what you have experienced, and continue to experience, in struggling with cancer and EDS. You have gone through so much, and you still radiate love and intelligence and engagement and compassion and joy, and you still write ferocious poems. For myself, I have always experienced my body as problematic, and not necessarily at one with my mind and spirit. How could it be otherwise, when the female body, the queer body, the disabled body, the body that does not reflect the cultural ideal, is so problematized? Maybe one reason we’re here is to struggle through the notion that the body is both precious and the site of so much suffering. I know there was a time, as a small child, that I experienced at-oneness with my body and with the world. Alienation came later, probably when I was handed the mystery of my dad’s winnowing and then de-souled body, and maybe most acutely with adolescence, as is true for many of us. It is then my body became a commodity, a ticket, if conventionally beautified, to the good stuff, like love and touch. As I have evolved as a body and a mind and imagination, I have felt both protective of my body as it is, and like it’s an impediment—maybe especially in the era of covid, which we pretend does not exist. The notion that the body “compresses the soul” feels right to me, in that it functions like form in a poem. Lyric compression. Body and soul. I’ve never written poems without a pronounced, even performed, awareness of and inclusion of my body, such as it is. We write with all of ourselves, at our best.

Jennifer Franklin: In an interview you did with Kaveh Akbar in 2016, you said, “I did feel like something that could be trampled, and was trampled. And I was very open, erotically open, in a way that I probably haven’t been since, at least until recently. I transferred that libido and openness to the page.” Can you speak a little about transferring the libido into the writing? It sounds a lot like the Jungian idea of integrating the conflicting parts of the personality. There is something so freeing about this idea, and I wonder how it has changed your work?

Diane Seuss: Wow, even though the interview with Kaveh was only 8 years ago, those comments I made seem lifetimes ago, Jennifer. Maybe I was in menopause! I did experience a re-awakening, post-divorce, and it was as problematic as my previous libidinal awakenings—adolescence, college, and my years in New York, all of which were luminous but messy. I’m interested in art as an expression of libidinal energy—mediated and mitigated by what has been called ego and super-ego, or the ethical self. Maybe form is the super-ego, the compressive force. (I think I’m that to my dog, Stella, who rolls her eyes a lot at my role as the limit-maker.) I’m wondering if most writers experience that full-body engagement while in the heat of creation. I think what I may have experienced in my earlier years, when writing a poem, was full-body emotion. My work has moved into a valuing of coolness, and objectivity, both of which could also be forms of libido. Libido in the walk-in freezer of a liquor store on the state line.

Jennifer Franklin: I often think of Gregory Orr’s thesis that all poetry comes out of suffering and that writing it is an act of survival. In A Primer for Poets & Readers of Poetry, he writes, “To me, poetry is about survival first of all. Survival of the individual self, survival of the emotional life…when poets go back by way of memory and imagination to past traumas to engage or re-engage them, then those poets are taking control—are shaping and ordering and asserting power over the hurtful events. In lyric poems, they’re both telling the story from their point of view and also shaping the experience into an order (the poem) that shows they have power over what (in the past) overpowered them.”

I also think about Edward Hirsch’s anecdote that the act of writing about his son’s death did not serve as catharsis but the act of making a book-length poem about this tragedy did. What is your feeling about the concept of poetry as survival and how has writing about your father’s death and other difficult losses in your life changed over the years?

Diane Seuss: Gregory Orr’s work on poetry and trauma has been crucial to my writing and my teaching. This part of the final sentence you quote—“shaping the experience into an order (the poem) that shows they have power over what (in the past) overpowered them”—is central to Orr’s own poems addressing the trauma of the accidental death of his brother, in a hunting accident, when Orr was a young boy, and to my own writing on my father’s illness and death when I was a child, and on my son’s addictions and struggles. I love the inference that it was Hirsch’s ambitious act of writing a book-length epic on his son’s death that brought him catharsis. There is something to be said for the opera—for putting forth the intention of creating something that is nearly beyond us. I have such admiration for both Orr and Hirsch, and have learned from them, and from you. Having the lifelong project of knowing my father via poetry, really since I was a child, has been a saving grace. Yes, he is an icon, an archetype, in all of my books, but he was also—simply—a human being. I could not know him in life, once he was underground, but I absorbed him into my imagination. This allowed for an ongoing relationship, albeit one-sided. In Modern Poetry, there’s a decided shift in that relationship, a movement toward distance and objectivity. My father evolves with me. As I wrote in one of the sonnets in frank, when I was very young the two of us went into a House of Mirrors at a carnival. I kept losing him, and then finding him, only to crash into myself in the mirror that held him. He is a ghost, a mirror, an archetype, and a man.

Jennifer Franklin: In “Bluish,” you write, “Inside, Diane, you suffer, / and your suffering is you.” How do you approach grief and suffering in your work? Is this book a departure in terms of how you treat loss? In “Rhapsody” you mention “trauma [is] a word, I’ve grown to hate.” There seems to be almost a clinical interest in the earlier versions of the speaker, as if those earlier selves are similar to characters in literature. Does your treatment of writing about difficult subjects relate to your comments about your interest in coldness and objectivity?

Diane Seuss: I imagine many writers feel this; every life phase, every book, uncovers another layer, debrides the burn more deeply. I’m not sure if I’m getting more honest—like nothin left to lose—or if the tone or quality of the honesty has simply shifted. The speaker in Wolf Lake, White Gown Blown Open, my second book, is “me,” but a very different self than the one I currently occupy. That “me” is barely recognizable to myself. The self that I have arrived at in Modern Poetry declares things I wouldn’t have thought or written in earlier books. For instance, the line about trauma, which is unsettling to me and probably to many readers, though it is something I feel sometimes in relation to my own life. It’s also part of the current speaker’s swag, their self-protective cynicism. One’s whole lexicon shifts, with time, with life. Maybe we earn a level of honesty we didn’t have access to before. As you imply in your question, the speaker is always a literary device, even if it reflects, deeply, an aspect of self. Whitman, I suspect, was not the “I” of “I celebrate myself, and sing myself,” though the “I” in the poem was an aspect of Whitman, enlarged, flattened, and articulated. The vibration of that line communicates truth in a way our daily, walking-around selves, cannot. We dilute ourselves in order to function. The self is already an odd construct, made odder and more mysterious by its use in the pursuit of truth on the page. Yes, the speaker in Modern Poetry gave me the gift of uncovering objectivity as a value, and a way of seeing. I view it as a gift from the dead that allowed me, during a dark time, as Roethke writes, to come to terms with poetry and with love.

Jennifer Franklin: Honesty and authenticity are two ideas that come up a lot in this collection. “I wasn’t a mean drunk then, / just honest.” “A cobbled mind is not fatal. / You have to be willing to self-educate / at a moment’s notice, and to be caught / in your ignorance by people who will / use it against you…But your poems, with all of their / deficiencies, products of lifelong observation / and asymmetric knowledge, will be your own.” And in “Juke,” “All I can say of it was that it was real.” I have heard you speak of working hard on poetry, of approaching it as working people approach a job. There is a thread through a lot of these poems, not only of the labor of poetry but also of the reaching for something that is just out of one’s grasp. “I would like to have better ideas than the ideas I have.” “There is an idea I am reaching for but like a jar on the top shelf and no step stool, I can’t leap to it.” “Language comes hard.” Can you talk a little about your creative process? How does poetry come to you? Do you sit down and write a little every day? What is your revision process like?

Diane Seuss: Well, language does come hard to me. Shaped language. Formed poems. For me, they’re not just talk; they are not casual, even if they perform casualness. Art-making of any kind is tough, as I know you know. I think it should be. There is so much to consider, so much to be done. And we must wrestle with the imagination, even as we use our minds, such as they are, to use craft in the service of the poem. We always need to be reaching just beyond ourselves, I think. It’s difficult, but no more difficult than what my people do every day of their lives, with much less support and glory. Pipe fitters, rail workers, teachers, gravediggers, grocery store cashiers. I learned how to write poems as much from workers’ self-discipline and guts as I did from classes and books. I have a penchant for the real, even as “real,” in a poem, is stylized, languaged, and therefore a facsimile of the real. I have never written every day. Not only has the nature of my life not allowed that, I don’t think it would be my jam even if it was. I write in my head daily, though, and when I turn to the page, I’m ready to lay down the lines. And I revise as I compose. There’s a point of entry, and a period of intuition and understanding, and I need to capture it before it drifts on to some other lucky bloke.

Jennifer Franklin: When you and Jane Huffman read together and discussed your new books, Jane mentioned that when you were her undergraduate professor you opened the door to what form can offer a poet and showed her that with form, one need never have writer’s block. Can you speak a little about what form has meant to you as a writer over the years?

Diane Seuss: Yes, I was lucky to work with Jane in the classroom, and she was the brilliant, alert sponge you’d think she’d be. When I taught undergraduate creative writing, we wrote in a form-a-week throughout the term. I’d teach the “traditional” iteration of a form, and show examples of contemporary improvisations with it. Inevitably, those who initially hated forms became hooked on them. When I was their age, I would have rebelled against anything constrictive, because—well, what did I know other than rebellion? As I’ve grown up, I have become more aware that poetry is form, and form is its salvation. Form is what the world is—a concept, brought into materiality. Our bodies are forms. The places where we live. The construction of a root system, or a worm. Yes, I rebelled, but we all must rebel, at one time or other, against god.

Jennifer Franklin: The act of writing about poetry is a thread throughout this book. The speaker grapples with what poetry means at this time in her life as well as in the context of multiple apocalypses. In “Curl,” the second poem in the mss you write, “it seems wrong / to curl now within the confines / of a poem.” “What can memory be in these terrible times? / Only instruction. Not a dwelling.” “Lately, / I’ve wondered about poetry’s / efficacy.” And “Poetry” asks, “so, what / can poetry be now? / Dangerous / to approach such a question/ and difficult to find the will to care.” The speaker goes on to meditate on the questions of truth “truth may involve a degree / of seeing through time.” and beauty (please don’t tell me flowers/are beautiful and blood clots / ugly” and wisdom, about which the speaker is decidedly against (“Maybe truth is the raw material of wisdom before it is conformed by ego fear and time… it’s really a kind of nasty enterprise.”) Without feeling you need to speak about what you have already said so powerfully in these poems, is there anything you want to discuss about the dual role of poetry in your life and the role(s) your think poetry might serve in the life of your reader(s) at this time in history that is so replete with strife, war, climate crisis, and imperiled bodily freedoms and precarious democracy at home and abroad?

Diane Seuss: Poetry, for me, is an instigator. The terms of engaging with writing poems instigate in me, demand from me, an honest confrontation with myself and with the world as I see it. This book, more than my others, calls out any previous hiding I did—hiding within the poem, within memory. The inference is that poetry reveals. It asks for a degree of personal courage. It is not a comfort station, but a fire engine. There are many ways to address/confront/engage with the perils of our time. Even reading your list at the end of your question is almost too much to bear. But if we write, we must address and engage and bear. My poems in this collection do not necessarily name the issues, but they are there in the very eco-system of the book. I might call my approach existential. The speaker grapples with a crisis of meaning, down to the very core, to the roots of their hair. Poetry serves its range of readers differently, of course. Some read poems for comfort, for distraction, for relief, for glee, for exposure to the harrowing, for empathy, for high comedy and low tragedy. When I write, I’m wrestling with the poem, not aiming to impart a particular message to the reader. Far be it from me! What I hope I construct is a corridor of truth-telling, insofar as I can manage it. In the process, when the book is passed onto the reader, the poems may impart a human connection. And I deeply appreciate anyone who lends their attention to my work.

Jennifer Franklin: You write in “Poetry,” Maybe there is such a thing / as the beauty of drawing near. / Near, nearer, all the way / to the bedside of the dying / world. To sit in witness / without platitudes, no matter / the distortions of the death throes, / no matter the awful music / of the rattle.” Can art be a balm even if it we shouldn’t look to it to offer wisdom? After grappling with what can poetry mean now and what is the efficacy of poetry, where have you landed?

Diane Seuss: I imagine it can be a balm, depending on the way it lands for a reader. It can also be a disturbance in the force! The poems I love the most are not comforting; they take off the top of my head, as Dickinson writes. They realign the molecules in the body. Sometimes, through the power of the lyric, which can be super-human, they do take us to the sheeted edge of the dying world, a place to stand even though we can’t fix it. To stand at that edge has, for me, been a lifetime struggle. It began with the last time I saw my father, at the sheeted edge of his hospital bed. The place I arrived in the book comes through in the sequence of poems in the last section, which make their way to a form of self-love, a form of love of the other, to objectivity about…what we once were and can be no longer. To objectivity about the dead, about death itself. By objectivity here, I don’t mean a clinical distancing, but something more like enlightenment. And in the final poem, I imagine the implication (though I don’t want to over-interpret for the reader) is that, despite poetry’s foibles and frailties, there is no arguing with “Ode to a Nightingale.”

Jennifer Franklin: Even though Keats is the named spirit that haunts these poems, I wonder if both Whitman and Dickinson are here, too—in Whitman’s great love of the world and your great compassion. And in Dickinson’s solitude and interiority and in your repeated invocation of letters. This book feels like a love letter to your reader and to the world. Were you thinking of them at all in the writing of these poems? Why did you decide to dedicate this book, “For my Reader?”

Diane Seuss: Whitman and Dickinson are always there, like the lions in front of the public library. Whitman teaches me to take up space, Dickinson, compression as a pathway to power. Whitman, to embrace what is. Dickinson, to follow an interior mystery, to create the world. Yes, Keats is the guide and mirror in this book, for more reasons than I can name. His early death. His doubt, at the end, about his legacy in poetry, about what it had all come to. And most centrally, his notion of Negative Capability, in which an artist is “capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” The opening poem of Modern Poetry, “Little Fugue State,” situates the speaker in a deep mystery, an amnesiac state, a spiritual lostness, a dissociative embodiment, an abject disconnection from “what my scrawling meant.” From this state of being, this Negative Capability, the rest of the book unfolds, and by the end, perhaps does come to both a place of reason, or momentary enlightenment, and that something else—the nightingale. The book’s dedication, “For my Reader,” is both objectively and lyrically true. The willingness of the reader to connect with the work has been astonishing to me, and has absolutely allowed me to continue moving forward as a writer. The human connection with readers/writers has visited me in my necessary loneliness. And this book, in particular, attempts to address the complex pain of now on behalf of others, not only myself. I also specify, in the acknowledgments at the back of the book, that “my Reader” is likewise Graywolf Executive Editor Jeff Shotts, who has become increasingly important to me as the personal and archetypal “other” who receives my work on the other side of writing it. One must have a human connection, after all. Dickinson had Thomas Wentworth Higgenson, to whom she wrote, alongside four of her poems tucked in an envelope, "Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?" I have felt her question was coyly performed. She knew her voice was alive. Higgenson was an ambivalent mentor, to say the least, urging Dickinson against publishing her poems because of their unconventional strangeness (i.e. their genius). I have been beyond fortunate to have Jeff as my Reader and editor, as he is much more approving of my doing what I need to do. We have grown to trust each other, and that, for me, is rare.

Jennifer Franklin: Mentorship has been one of the most important aspects of my life, not just my writing life. I was lucky two have two incredible mentors—Arnold Weinstein as an undergraduate and Richard Howard in graduate school—who saw something in me even though I didn’t yet see it in myself. And now, because I have experienced this tremendous gift, I am driven to be that person for the students I teach. I have heard you speak about your mentor Conrad Hilberry and, in the acknowledgements of Modern Poetry, you mention him and Stephanie Gauper for teaching you there is such a thing as a woman writer. I see the way you mentor people in the poetry community now who aren’t even your students. It seems meaningful for you to share what you have learned and support and elevate emerging voices. Can you speak a little about why that matters to you and how you approach it?

Diane Seuss: Yes, Jennifer, it still amazes me that you were taught and mentored by Richard Howard, and so many other luminaries. It comes through in your work and in your presence. Your phrase “who saw something in me even though I didn’t yet see it in myself” is key, I think, to mentoring. As with Jeff Shotts, I got so much from Conrad Hilberry, who found me under a cabbage leaf, at age sixteen. He saw me. He remained present, and supportive, even through my numerous screw-ups—necessary screw-ups, I would add. Mentoring isn’t a blanket activity. Each person must be seen in their entirety, and for their unique needs. It isn’t charity, as it energetically feeds the mentor as well; that aspect of the relationship must be acknowledged, lest it become unconsciously parasitical. As you well know, we give what we got—and more. At our best, we give what we needed and never received. And then, as in Jane Huffman’s case, and Aaron Coleman’s case, among many others, thank the spirits, we are outgrown.

Jennifer Franklin: What are you working on now? I heard a podcast where you said you were researching Burlesque and I was curious how that might manifest in your work.

Diane Seuss: Well, I confess that post-Modern Poetry, I’m still feeling my way. I’m writing short, thin poems with big titles—fancy that. They are deeply, sometimes comically oriented toward sound and rhyme. I remain interested in the literary burlesque—in voice-driven, parodic poems—and maybe these creatures I’m writing now do reflect that interest in some way, in the way they play with language, in a comic manner, even when they engage with serious subjects. But, Jennifer, I’m still finding my way. I am open to guidance from above, and below.

Diane Seuss is the author of six books of poetry, including Modern Poetry; frank: sonnets, winner of the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and the PEN/Voelcker Prize; Still Life With Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize; and Four-Legged Girl, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. She was a 2020 Guggenheim Fellow, and in 2021 she received the John Updike Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She lives in Michigan.

Jennifer Franklin is the author of three full-length poetry collections including If Some God Shakes Your House (Four Way Books, 2023), finalist for the 2024 Paterson Poetry Prize. With Nicole Callihan & Pichchenda Bao, she co-edited the anthology, Braving the Body (Harbor Editions, March 2024). In 2021, Franklin received a NYFA/City Artist Corps grant and a Café Royal Cultural Foundation Literature Award. She teaches craft workshops in Manhattanville’s MFA program and 24 Pearl Street of Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center. For the past ten years, she has taught manuscript revision at the Hudson Valley Writers Center, where she serves as Program Director.