In Their Own Words

Oliver Baez Bendorf on “Becoming Particulate”

Becoming Particulate

When a voice met the resonant frequency of the object,

when the song crashed into glass as invisible waves,

at last I began to vibrate. Finally! I exploded like a garage

window the year the rooster sang. What was it that rattled

me so astrologically? Or does it matter only

that I was rattled, propelled from my brittle bunker

into a new position, compromised now by such beauty

as mist caressing a mountain, or how heavy

the satchel of ashes lands against my ribcage? I pray

my recollection of the neighbor dissolves into nothing

when we leave this town, that however much the song

I love rattled him too, that he forgets me entirely

for he exploded in a different way. Something

about my mother is I learned to dry plastic baggies

upside down. Though I’d never plant grass in a place

I’m meant to stay, I try to reach every last seed

with my mouth now the promise of leaving

glows the horizon. Learning to speak the language of mums,

I ask myself how the fear of small

particles affects my everyday experience. Today I give

thanks for the way, in pestilence, living has gone on.

I remember Dilly by her bones, now pulverized, like

dust of the dead, in whose light we still read our future.

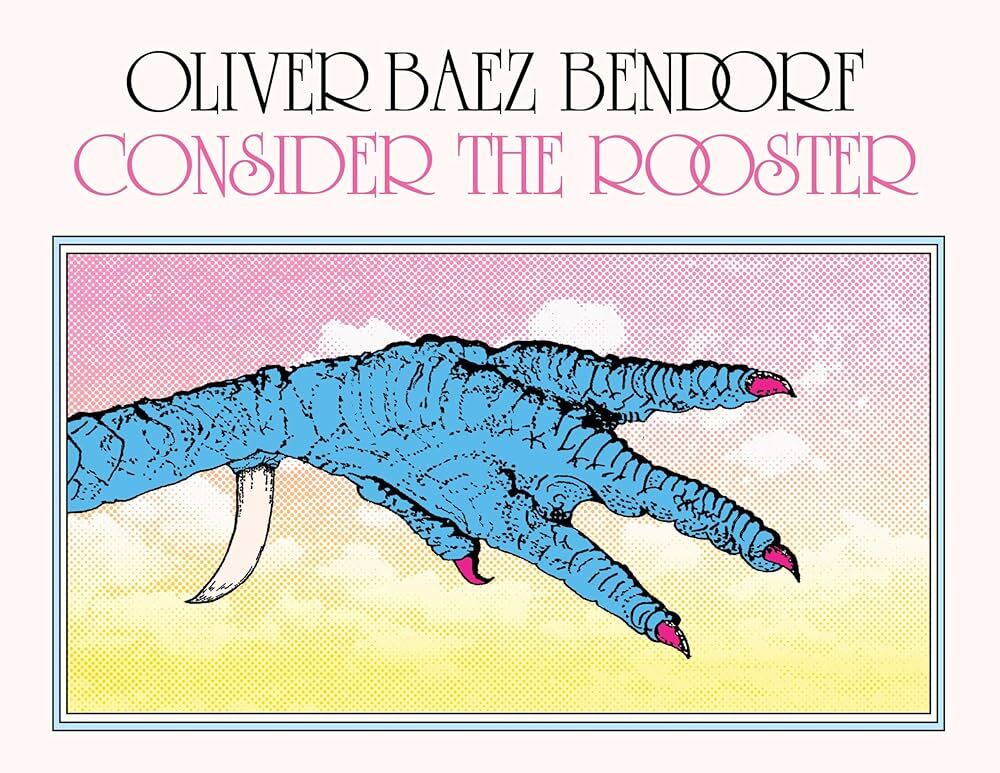

Reprinted from Consider the Rooster (Nightboat Books, 2024) with the permission of the author and publisher.

On “Becoming Particulate”

For many months, “Becoming Particulate” opened the manuscript of my third collection, Consider the Rooster. Though it ultimately became the second poem, it introduces central ideas: change, resonance, and the body.

When the WHO declared Covid-19 a pandemic, I found myself in Kalamazoo, Michigan, tending a no-mow meadow. I was on the tenure track, sharing my days with a pandemic pod that included a flock of backyard hens, one miniature rooster, and my house rabbits, Dilly and Claude. Life was complex, but the animals were my constant. Walter, the rooster, became a defining figure of that time, his crow announcing each morning with aplomb.

Walter's crow was an event, a daily meditation resonating through that little patch of land. It cut through the air not so much to be heard as to be felt. The phrase “becoming particulate” came to me first as a whisper, then an echolalia. It came as a counterpoint to “becoming articulate” – not as a call for clarity of utterance but as permission to scatter, to transform, to touch one another in ways beyond words. Walter's crow rattled me out of the ways I had made myself smaller, trying to fit into someone else’s dreams.

He brought joy to many: an older couple who called to him daily on their walks, their faces lighting up when he called back; the guy who, hearing his crow, said, “Is that a little bantie?”(bantam rooster), recognizing the sound from his childhood farm. Yet one neighbor saw it as an infringement on the quietude of his life. Walter's crow revealed who feels entitled to dictate which presences are allowed, exposing the unspoken rules of who can occupy space and make their presence felt.

Tractor Supply had said there were no roosters among the baby chicks brought home. Yes, Walter was assigned female at birth and policed out of his neighborhood when his true self emerged. Sound familiar? Walter Mercado, miniature bantam rooster, mythological trans masc. He was beautiful, iridescent, tough as nails. He dazzled. He didn’t take shit from anybody.

Walter's crow cut the air, and the air was tense. Amidst pandemic and social upheaval, amidst widespread demonstrations against police brutality, Walter crowed. Fifty miles away, right-wing militiamen were plotting to kidnap Governor Whitmer. Meanwhile, someone at the city said complaints against neighbors had skyrocketed, with people walking the streets, calling in minor violations– bureaucracy’s little rules that regulate land use, rainwater collection, aesthetics, life itself. “Land of the free,” but for whom among us? Some of us must be brave, by necessity.

Walter's crow shook me from the inside out, once I let it. That’s all a crow wants: for you to change. As Meg Day writes, “Silence is just another ableist metaphor.” Resonance isn't always about sound. It's a sensory and environmental experience. Walter's crow wasn't filling a silence; it created an energy that moved through my body, the meadow, the neighborhood.

The poem describes the “garage window” glass shattering, “mist caressing a mountain,” and “the satchel of ashes” heavy against the ribcage. These images echo Walter's crow and its message: “Be changed.” Everything changes form–what a relief. In some ways, change is the path of least resistance, but it also meets resistance, making change itself an act of resistance.

Increasingly, we live in a power structure that demands neatness and conformity. Walter's crow, and this poem, became about a refusal to be boxed in– an assertion of presence, of the right to resonate, to refuse to cohere into clarity, to scatter, to become, to know one's own sacredness.

In the end, we scattered. I still miss his song. I’m singing now. Oh, Walter. And the Walter in me, and in you.

To become particulate is to embrace the breakdown of old forms. It’s to understand we are constantly in a state of becoming, resonating with each other, other living beings, and our environment in ways that defy articulation. Maybe Walter’s crow calls on us to listen—not with our ears, but with our whole bodies. To become particulate is to allow ourselves to be moved by what stirs within us, even when it shatters us into something new, “propelled from my brittle bunker.” I still hear its call—to embrace our scattering, to dissolve into the world, and to emerge transformed.

Citation:

Day, Meg. “Sound Consequence” Sound Consequence | The Poetry Foundation